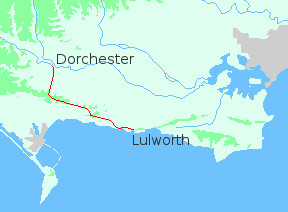

Lulworth lies a few miles south of the main Bournemouth to Dorchester railway line. A solitary bus leaves Wool station just after nine, wandering through the lanes to the village and on to the Cove. It stops outside the visitor center.

In summer Lulworth is a place best avoided. Vehicles crawl along the approach road; excited kids scamper about. And down from the car park a hot mass of humanity moves - past cottages and wooden shacks selling ice creams and beach balls and souvenirs, down to the sea, to jostle for space on the narrow, pebbly beach.

On a cold morning in spring I had the place to myself. I followed the narrow lane to the water's edge, on the chance that there might be somewhere selling coffee (there wasn't - Lulworth doesn't do earlies). I had a young dog with me, who had never seen the sea. The waves, as they snapped at the shingle, she viewed with suspicion; but she was entranced by the new and varied smells drifting on the breeze. I let her explore for a while; then calling her away from the tangle of rotting seaweed she was investigating, set off for Durdle Door.

From the visitor centre a well-made track clambers up and over the horizon. The view as you reach the top of the rise is sudden and dramatic. Up ahead the cliffs curve round to Weymouth. Beyond the town a grey shape looms: Portland, Thomas Hardy's "Isle of Slingers"; that strange eruption of limestone he so aptly called "the Gibraltar of Wessex".

Inland the land rises to a long chalk ridge. Near Lulworth it is spoilt by a holiday camp, where caravans march in dreary lines. As you approach Durdle Door, however, the track turns away and the camp is left behind.

The rocky arch of Durdle Door was carved over millenia by the restless sea. Tbe waves still gnaw at the pillar suporting the span, and one day - in a hundred years, or a thousand years - it will fall. But for now it stands, an outcrop of limestone sheltering a small bay.

From Durdle Door you can follow the coastal path to Weymouth. My business, however, was with the chalk; so I turned inland, on a footpath which sloped up the side of a dry valley. This is Scratchy Bottom; and I might have recognized it, as it was used in the opening sequence of one of my favourite films. In the 1969 version of "Far From The Madding Crowd", Bathsheba Everdene rides along this very path!

Untroubled by cinematic ghosts I climbed the ridge. While the coastal path traces the line of the cliffs, climbing and dipping as the land rises and falls to the sea, the inland track keeps to the high ground, maintaining a level course through wide, expansive fields. This is lonely country: in the miles between Lulworth and Dorchester I hardly saw a soul. Southward the settlements are few along the margin of the sea. To the north the downs are empty except for a few quiet farmsteads. I thought of one of Hardy's stories as I walked - "The Distracted Preacher", which was set in these parts. It was easy to imagine the smugglers transporting their cargoes by night, over these isolated hills.

After several miles the track became a narrow lane. For the first time since leaving Durdle Door it made a meaningful descent, down to a dairy farm set in a deep, wooded valley. After the clean, wind-scoured upland the warm smell of cows was overwhelming. Then the track climbed again, emerging onto the ridge in the vicinity of Poxwell Manor.

Beyond Poxwell the ground levels out once more. Here the downs are less expansive, the graceful sweep of the chalk broken by dry-stone walls. For the most part the land at the foot of the ridge is hidden; though occasionally there are views of Weymouth, the elegant curve of the Esplanade backed by a sorry sprawl of brick. The bulk of Portland is closer now, its northern ramparts visible across the water. The track pushes on, through stony fields washed by wind and sunlight, and the strange salt smell of the sea.

At Came Wood I turned off onto a narrow footpath. The wood lies on the sheltered side of the ridge; in spring a haunt of bluebells and butterflies. Soon I came out of the trees and crossed a broad field sloping to a little valley. A quiet track led along the valley floor, winding languidly down to Winterbourne Came, where the Dorsetshire dialect poet William Barnes was once Rector.

Winterbourne Came is a private estate, with a manor and a few adjoining cottages. The path to the church branches from the lane, by the wall of a kitchen garden. After long miles over windy uplands the seclusion is uncanny. In the quiet churchyard, alone among the dead, there's little that speaks of the present.

Beyond the village is a low ridge. On the further side, quietness comes to an end. The last mile is accompanied by the thunder of traffic circling Dorchester. Like a defensive wall the ring-road encloses the southern suburbs, separating town and countryside. I made a somewhat perilous crossing, dodging the speeding lorries, then wandered through quiet streets to the centre of things.

If you enter Dorchester from the north you step straight into the heart of the town. Approaching from the south there are avenues of brick, somnolant terraces where nothing seems to happen and nobody is ever about. This is Victorian suburbia: shabby-genteel housing thrown up in the 19th century to meet the demands of the new middle classes; poor in imagination and execution. I find it all rather depressing.

There was no temptation to linger, so I hurried through the streets to Dorchester South, and the train back to Wool.