I awoke at first light, and not with much enthusiasm. It was a damp and murky morning. The fog had settled on the trees and bushes and was dripping onto my sleeping bag. I had set up the bivouac on a shallow slope, and in the course of a restless night must have slithered down and out of the open end. Not the most cheerful start to the day.

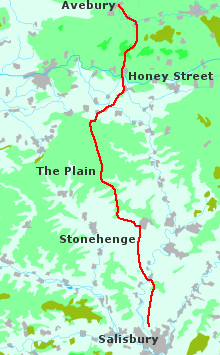

By the time I had coaxed my soggy belongings into the rucksack and munched some chocolate it was raining in earnest. I pushed through the undergrowth, stepping carefully on the greasy chalk, and came to the edge of the wood. North and eastward the rolling fields were vague shapes in the mist; to my left the wet ground fell away to the river; and beyond it the shadowy edge of the plain loomed. It was not a heartening prospect. I limped off through the falling rain, distinctly underwhelmed by it all. A pleasant stroll, no doubt, the Avon valley, but at six o'clock on a wet morning it was hard to feel much enthusiasm. The track ran on past fields smelling of rotting sprouts, through woodland choked by nettles. There did not seem to be anything worth looking at.

At the end of a depressing hour came a change in prospect and a change in the weather. The cloud-wrapped sun rose and gained strength, and the rain slackened and died. It was still damp, but at least I could peel off my sodden waterproofs. I felt better as I dropped down to the river, crossing the stream by the old sluice gates of a watermill. On the other side of the valley the scenery improved; the untidy fields gave way to swelling pastures of cropped turf. Racehorses cantered up, lithe muscular creatures with thin intelligent faces. I followed a shallow valley that wound its way out onto the swollen chalk. The air was heavy and still, but as I climbed a cool breeze sprang up, brushing away the mist. I reached the crest, where Bronze Age barrows clustered in a broken wall; then suddenly, unexpectedly, far ahead I saw rising up out of the grass the grey weathered sarsens of Stonehenge, bright in the morning air.

It was the best part of a mile to the visitor centre, and I pushed quickly over the plain, intent on breakfast. I was extremely hungry and none too warm. As it was only ten in the morning the car park was deserted, but at least the cafe was open. I sat hunched up on a bench with a sandwich and a hot cup of coffee, chatting to a pleasant young lady conducting a survey on behalf of English Heritage. There were various plans afoot for re-routing the A303 away from the stones and they were testing public opinion. Perhaps a tunnel, or re-aligning the road. Five years on nothing seems to have happened, but maybe the guardians of the site will finally get around to it. Stonehenge, sadly, has become the victim of its own renown. Fenced in, noisy, with turnstiles and souvenir shops, it looks like some wild thing caged for the amusement of passers by. It is sorely in need of some peace and quiet, and a little time to itself.

From Stonehenge the track leads northwards to Larkhill, crossing the line of the cursus. You can just make out the banks of this enigmatic monument in a field to the left. It was once assumed to be Roman but is now known to be much older, perhaps predating the first phase of Stonehenge. Like much of prehistory it is not fully understood. Its importance, though, seems clear from the scale on which it was laid out and the labour that would have been needed to achieve it.

I worked round the western edge of Larkhill camp. By the side of the dirt road I came upon a line of huge tanks and personnel carriers. As I approached them they snarled into life and thundered off, throwing up a flurry of dust. Past the camp I was walking west, and I could tell that the wind was from the north; the trees to my left were stained white. Long swathes of coarse grass had been laid low with the passing of the monsters. The tracks looked like the imprint of dinosaurs.

I felt like a pint before tackling the dry interior of the Plain, so I approached the Bustard Hotel. I was surprised to find it still closed at half past eleven, and was wondering what strange hours they kept in that remote corner of Wiltshire, when a boy messing about on a bike reminded me that it was Sunday. So I sat myself quietly down by the side of the road until noon. By the time I left the inn the sun had cleared away the last reluctant clouds and it was growing warm.

To walk on Salisbury Plain is to glimpse something of a vanished world. As you cross it there are hints of the past, suggestions of what these downs might once have been. Some areas are abandoned to farming, and there is a constant military presence; distant targets on the gunnery ranges, security barriers, warning signs. Enough, though, survives to give to the whole Plain a unique atmosphere. There are deep valleys that have not been ravaged by the plough, and wide slopes of unfenced turf. There are butterflies and chalk flowers. There are long barrows dark against the sky. And the wind wanders at will through the grass. For a moment, I wished that I could do so too, but then I came to a sign that read "DANGER. DO NOT LEAVE THIS ROAD. DO NOT TOUCH ANYTHING. IT MAY EXPLODE AND KILL YOU". The grass around it was blackened by fire, and one end had been blown clean off. Point taken.

In the lonely heart of the Plain, where three roads meet, an old signpost still survives. One arm points back to Salisbury, the others onward to the Vale of Pewsey. I remember it still, as marking a new phase of the journey. The New Forest and the hills round Salisbury had seemed comfortable and familiar. They were no more than a long day's walk from where I lived, and I knew them well. That sign was the start of something new. It spoke of places known only from the map.

For the first time I began to feel truly self-sufficient. If you are out for a few hours you don't have to worry about wind or rain, as home is never far away. You don't need to eat or rest; you can rely on stored energy. But walking day after day is different. Eventually you have to match the intake of food to the expenditure of strength. There are no more reserves. You must also strike a proper balance between travelling and sleeping. And if you are camping out you must find shelter, and stay warm and dry. The first part of the journey was a sprint, forty-five miles in less than two days. But on Salisbury Plain, I slipped into a different gear. I moved more deliberately from then on, covering around twenty miles a day, eating more and resting more. It was payback time.

From the signpost to Redhorn Hill the road was hard underfoot. It was deeply rutted, and the winter mud had set like stone. I was glad to reach the footpath that descends into the Vale, and to swap my heavy boots for a pair of light training shoes. Thus shod I made much better progress. The breeze died away as I drifted down, through fields already rich with the new growth of spring. Among the lanes the air was warm and still. Mingled with the fresh green smell of the grass and hedgerows was the dry and dusty scent that heralds the approach of summer. It was a languorous afternoon; the faint hum of insects hung in the deep silence. Placid cows gathered in patches of shade around the margins of deep meadows, ears twitching, tails flicking lazily at the buzzing flies. I felt sleepy. I had been awake since six, and could happily have lain down somewhere and dozed in the sunshine. But I resisted the temptation to idle away the afternoon and pushed on along ribbons of hot tarmac, towards the hills that lay along the north side of the Vale.

Over the canal at Honey Street and past the village of Alton Barnes the landscape changes once more. The footpath leaves the road, climbing abruptly into the sky. As I plodded up a steep spur of chalk the land fell away around me. I reached the plateau by Adam's Grave long barrow, and looked back. The declining sun was away to my right, casting long shadows over the lower land. To the south I could make out the Plain, a long dark line on the rim of the sky. I turned and gazed out ahead. The grass swept up in a green wave for half a mile, then broke on the crest of the ridge and drained away, down in the direction of Avebury.

A team of archaeological students from one of the universities was carrying out a resistivity survey of the barrow that afternoon. They had planted rows of metal probes, connected by electrical cables, in order to measure the differences in conductivity caused by buried features. They showed me the results of the various traverses plotted onto a laptop, the internal stone structure of the burial chamber clearly visible as a band of bright colour on the screen. They also answered, politely and patiently, my questions about ditches and stone circles, barrows and Stonehenge, the significance of Avebury, and the sequence of things in that rich archaeological landscape. A friendly bunch, and a pleasure to talk to after so many hours of my own company.

On the way up the long slope to the Wansdyke I rested for a while on a convenient stile. Some lambs caught sight of me and scurried through the long grass. They must have been recently separated from the ewes, and were not old enough to have acquired a fear of humans. They butted my legs, seizing the loose ends of my clothing in an attempt to suckle. One was particularly affectionate. I scratched its head, burying my fingers in the tight curls around the neck and shoulders. Then I shook them off and picked up my pack. They followed me half way across the field.

Night was falling as I crossed the Wansdyke. The bank and ditch were half hidden by thorn bushes, dim in the failing light. The deep-rutted track ran for a short way through a wood, then emerged into the open. Ahead, I could see the valley of the Kennet. From the path sloping down from the ridge I caught sight of the conical mass of Silbury Hill, away to my left.

As I approached the village of East Kennett I was starting to think about somewhere to camp. It looked from the map as though there might be a suitable spot down by the stream, but when I got there and looked about the ground was muddy and nettle-strewn. So I pushed on to Avebury, following the avenue of stones that stretched out over the grass. I had planned to get something to eat at the Red Lion, but I felt too tired to bother. I just wanted to lie down somewhere. A footpath led back south along the stream, through a field of stubble. I followed the fence line up to the broad crest of Waden Hill; and there, beneath the stars, looking out over the world I slept.