There probably hadn't been anyone on Hungerford Common all night. There probably wasn't another person within half a mile. So wasn't it just typical that the woman should walk past as I crept shivering from my sleeping bag and was endeavouring with frozen hands to pull on my trousers! A pleasant soul with a cheerful booming voice and a pack of dogs, she seemed amused at my being where I was. We talked for a while about the joys of the outdoor life; then, stuffing my wet gear into the rucksack, I walked into Hungerford, boots flapping. My fingers were too cold to knot the laces.

It is astonishing, how much food you actually need when carrying a rucksack for several days at a stretch; particularly when it is cold, and you are sleeping rough. When I am out walking I degenerate into a sort of junkie, desperate for the next greasy fix. Normally I eat a fairly healthy diet; but that morning, in the half-light of the dawn, I could think only of eggs, bacon and buttered toast. I was cold and extremely hungry. I did not want muesli or orange juice. After a night on the Common, I wanted the works.

What I got, sadly, was rather different. A big problem when out on foot is where to eat early in the morning. You invariably wake at first light, and are on the move by six or six thirty, especially if you are sleeping on someone else's land. Most cafes do not open until nine or ten o'clock, when sensible people are leaving the warmth of their beds and turning their attention to the matter of food. In cities and by main roads you might find something, but small country towns are hopeless. Perhaps Hungerford contains early morning eateries, but I found none. And it didn't really look that sort of place. In the end I had to make do with a Scotch egg - and I can safely say that a Scotch egg on a raw cold morning down by the lock is not an appetizing breakfast. I managed about half of mine. Then, hurling the remaining fragments of breadcrumbs and meat into the canal, where they were ignored by a pair of mallards, I heaved my pack onto my back and set off. I was not in the best of humours.

For several miles the way lies through ancient meadows. The canal here is lifted up a gentle slope by a series of old wooden locks. Smooth turf runs down to the water's edge, soft underfoot. At first I was too cold and miserable to look at the scenery, but gradually as I walked my resentment subsided. Behind me, the sun like a huge pearl rose slowly through the mist. The wind dropped and it grew warmer. I crossed fields of spring flowers where lambs suckled, tails quivering ecstatically. The light broadened; and, with circulation returning to something like normal, I began to feel less sorry for myself.

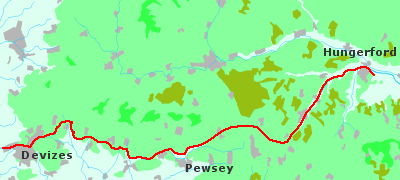

Beyond Hungerford, canal and river part company. The Kennet runs westward to Marlborough, while the canal bends away south of the hills into the Vale of Pewsey. I passed the pumping station at Crofton, one of several built to replenish the waters lost as boats descend through the locks. A mile and a half further on I reached the watershed, where the canal breaches a spur of land by way of a tunnel and emerges at Burbage wharf. This is the top pound, the highest point of the walk. From here, it is downhill all the way to Bath.

That morning I could see little of what lay about me. Grey slopes, sheep-haunted, ran away through the mist. Rooks squabbled somewhere in the treetops close by. I was approaching the chalk country, a wider, wilder landscape. Alone in a vague and shadowy world I wandered in thoughts of the past. Winter, when the downs streaked with snow stand out hard and clear in the frosty air. The cry of lambs in the spring, and the deep, answering call of the ewes. Swelling grasslands and broad pastures burnt by the summer sun, where skylarks tumble in the breeze and beech woods cling to steep escarpments. High hilltops with views to wide horizons, and nights under the stars. The hours passed like a dream, and at noon I reached Pewsey wharf. Outside the inn I swapped my boots for a pair of training shoes, and dumped my pack in the porch. I couldn't do much about my mud-daubed trousers short of removing them altogether. Then, as respectable as I could make myself, I ventured in.

It was a friendly, welcoming sort of place. At the bar they asked me where I had been and what I was doing. Fortunately they didn't want to know why, which perhaps was just as well, since after Hungerford Common I was starting to wonder myself! It was a question that occurred several times a day, when I was tired and footsore and hungry. Why walk, when I could have taken a train?

I suppose the answer depends on what you are looking for. If the purpose of a journey is to arrive, then going on foot is a very inefficient means of doing so. Perhaps, though, walking is not about reaching some imaginary end, but about experiencing the present, whatever it may turn out to be. When you are out in a landscape you can't hurry. You go as far and as fast as your feet will take you. And you can't dictate what will happen. If it rains, it rains and you get wet. We are so much in control of our lives, so well protected from cold and hunger, that it feels strange to leave anything to chance. Travelling slowly, watching the passing of the countryside beneath a changing sky, is almost an act of faith. It is to let things be, just as they are.

At last it was time to go. Finishing my drink, and trying to stand, I became aware that the muscles in my legs had locked up. I could hardly move. I made it to the door, just, and hobbled back down the road to the canal accompanied by good wishes. The stiffness wore off after a few hundred yards, but it was a problem that was to occur for the rest of the trip. I crossed the bridge and turned west.

The miles from Pewsey to Devizes are the most rural and isolated of the whole walk. The railway line, which has run by the side of the canal from Reading, wanders off southwards. There are few villages. The canal itself hugs the northern edge of the Vale, following the meandering contours of the downs in a series of wide curves. The countryside here is broad and expansive; there is a sense of space which you don't experience elsewhere. To my right, steep slopes clambered up into the sky. Away left, across the lower lands, lay the dark line of the Plain and the long road to the sea. The mist had gone, and the afternoon was cool and clear. The weather was perfect for travelling on foot. After a meal and a couple of hours in the pub I felt on top of the world. I drifted along in a haze of cider, scarcely noticing the distance.

High above the fields stood the White Horse, cut into the swelling chalk. I came upon the curious inn at Honey Street, where I rested briefly. A woman sat in the garden holding a barn owl. The bird, apparently untroubled by the late afternoon sunshine, gazed at me solemnly. Then onward, past All Cannings and Horton; until, in a deep cutting, the canal enters Devizes. Twilight had fallen as I left the waterside and came into the town. I sat on a bench in a deserted, lamp-lit street, eating a massive portion of fish and chips. In the takeaway, I must have looked as though I needed it.

The night was dark and still. Light clouds mantled the stars. I walked out to Caen Hill locks where I stretched out on the grass, too tired to bother with the bivouac. It didn't look as though it would rain. I remember crawling into my sleeping bag, but nothing more. In the deep night I was dimly aware of voices close by. A couple were approaching, hand in hand. "Hush," whispered the girl, "there's someone sleeping here". They walked quietly past, and I drifted off to sleep, warm and at peace with the world.